Unemployment Cliff Looms As 9.1M Americans Set To Lose Aid By Labor Day

Pamela Mohar planned ahead for when her pandemic unemployment benefits end: With her last check arriving in early September, she and her partner have prepaid their bills through October. She's not sure what will happen next.

"Once that last check comes, that will be devastating not to know where the next check will come from," Mohar, 37, who graduated from Eastern Michigan University in April with a master's degree in creative writing, told CBS MoneyWatch.

Mohar, of Ann Arbor, Michigan, said she's been looking for a job since last fall, when she was working as a graduate assistant, but so far hasn't had any luck. Before returning to school, she had worked in retail and as a bartender — experience she emphasized when applying for jobs. But she suspects employers aren't willing to hire someone they think might move on if a better job comes along.

Mohar has cobbled together part-time work, but still qualifies for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA), a new program created by lawmakers in 2020 to provide jobless aid to workers who usually don't qualify for the benefit, such as gig workers and part-time workers. Once PUA ends, those workers won't qualify for any regular unemployment programs.

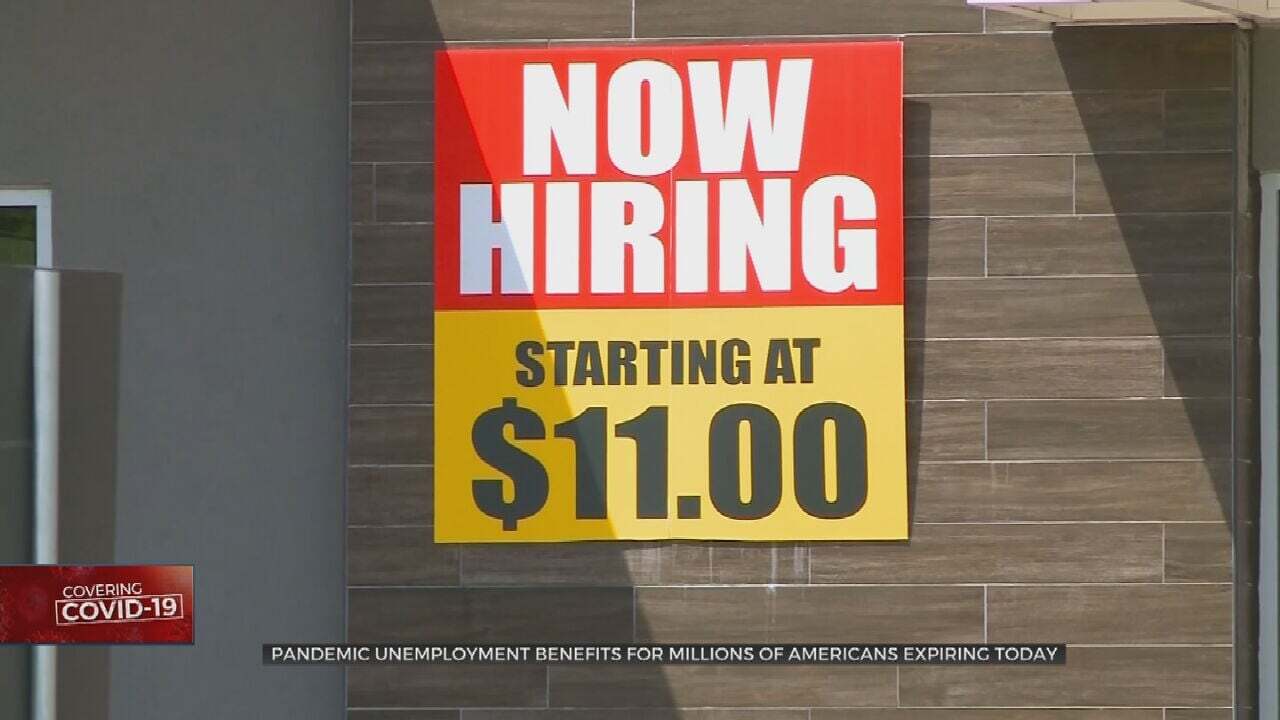

PUA is one of several pandemic unemployment programs that end on September 6, which just happens to be Labor Day. That will cut off 9.1 million unemployed workers from support, according to an estimate from the left-leaning Century Foundation.

This benefits "cliff" will disproportionately hurt workers of color and women with children, with the latter more likely than men to scale back work during the pandemic because of a lack of child care and remote school, noted Andrew Stettner, senior fellow at the Century Foundation.

"There has been almost no discussion about any real policies to avert this or change this, and like a lot of things in the pandemic the scale is a lot bigger than in the past," Stettner said. "It's almost like a problem that didn't need to happen."

It doesn't appear any lifeline is in the works. CBS News contacted officials in all 50 states to see if they would be extending the enhanced $300 benefits or other pandemic unemployment programs, but the vast majority said they will return to lower pre-pandemic unemployment benefit levels starting next week.

Calling for reform

The Biden administration earlier this month said the pandemic unemployment programs will end as scheduled on September 6, even as coronavirus cases linked to the Delta variant surge. A White House spokesperson said Friday there are no plans to reevaluate the end of supplementary unemployment benefits.

"Twenty-two-trillion-dollar economies work in no small part on momentum, and we have strong momentum going in the right direction on behalf of the American workforce," said Jared Bernstein, a member of the White House Council of Economic Advisers.

The Delta variant is sapping some of that momentum, with job growth slowing sharply in August as COVID-19 infections soared. The investment bank Morgan Stanley estimated Thursday that the economy will grow at an annual pace of 2.9% in the third quarter, down sharply from its prior forecast of 6.5%. That decline largely reflects a pullback in federal aid spending and supply chain bottlenecks.

Nevertheless, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and Labor Secretary Marty Walsh are urging reforms, noting that the pandemic exposed "serious problems" with the nation's unemployment system.

It's unlikely that any reforms would come in time to help the millions of households that will lose their unemployment aid early next month, said Jenna Gerry, senior staff attorney at the National Employment Labor Project.

"We will see this cliff coming on September 6, and people will be left without supports for some time," she said. "What we need is long-term reform and we need it immediately — we can't continue with these temporary programs."

Some experts favor changing unemployment so that extra benefits automatically kick in when the jobless rate spikes and remains high or is elevated for certain groups, such as Black workers. The nation's jobless rate stood at 5.2% in August — lower than its pandemic peak of 14.8% in April 2020, but still above the pre-pandemic rate of 3.5%.

And hiring across the nation pulled back dramatically in August as a surge in COVID-19 cases caused by the Delta variant dragged down the recovery, raising concerns about headwinds for economy. Employers added 235,000 jobs last month, far below the roughly 700,000 expected by forecasters.

Advocates for unemployed workers also say pandemic unemployment programs should be extended until the pandemic is over.

"The end of the pandemic for workers will be marked by the recovery of all pre-pandemic jobs (we are still short 5.7 million jobs from February 2020) AND an unemployment rate comparable to February 2020," Stephanie Freed, executive director of ExtendPUA.org, said in a statement.

"Knife in the chest"

Among the government's temporary patches to the unemployment system was providing aid to parents whose children were in remote school, an issue that impacted millions of families who suddenly had to juggle remote education with work.

About 1.8 million women have dropped out of the labor force since the start of the public health crisis, pushing the labor participation rate for women to its lowest level since 1988, according to the National Women's Law Center.

Among them is Alicia O'Brien, a construction worker in San Francisco. She said she lost her work early in the pandemic, but remained on unemployment to help her three children — all under the age of 12 — with remote education. Because two of them have asthma and can't yet get the COVID-19 vaccine, she kept them home even when the schools returned to in-person instruction.

But with unemployment ending, she said she needs to return to work so she and her fiancé can pay the bills. But she worries about her children's health and whether she'll be able to continue working if their school is shut down because of the latest virus outbreak.

"Unemployment ending is the knife in the chest," O'Brien said. "It's, 'Get back to work,' and I don't have a choice."

In her view, the federal government should extend unemployment aid until children under 12 can get the COVID-19 vaccine.

"I feel very frustrated," O'Brien said. "The amount of energy and time and life change that every parent has gone through from leaving jobs, staying home 24/7 with their children, not being teachers, trying to do distance learning, trying to help the teachers that are trying to help their child. Why not stretch [unemployment] a little longer?"

Benefits cut could hurt consumer spending

More than half of U.S. states have already cut pandemic unemployment aid, providing a glimpse of what may be in store for the rest of the nation. Twenty-five of those 26 states that reduced benefits starting in June are led by Republican governors, who argued that the enhanced payments were keeping workers on the sidelines.

For now, the results of switching off that aid doesn't bear out such concerns. Instead of supercharging employment, the first 12 states that cut aid have seen job growth on par with the states that maintained aid, according to one study.

In a recent analysis of 22 states that cut jobless aid in June, only 1 in 8 unemployed workers had found employment by the beginning of August, according to economists at Columbia University, Harvard and other institutions. While that reflects a modest gain, there was a downside: Those states experienced a $2 billion decline in consumer spending due to the loss of jobless aid.

The September 6 cut will likely have a fourfold impact on consumer spending, with a reduction of $8 billion in spending during September and October, the researchers forecast.

The economic rebound may face headwinds due to the loss of unemployment aid flowing to millions of households, noted Stettner of the Century Foundation, who estimates that the expiration will result in a loss of $5 billion in aid that's currently flowing each week to unemployed workers.

"This is money you are taking out of the economy," he said. "From what we have seen so far, there are other factors that are impacting job seeking," such as the Delta variant and low vaccination rates in some regions.

More people are expressing hesitancy about returning to work as COVID-19 rates spike. About 3.2 million people in early August said they weren't working because they were concerned with contracting COVID-19 or spreading it, an increase of 30% from late July, according to Census Bureau data.

Counting her unemployment aid, Mohar takes home about $1,100 every two weeks, more than what she earned as a graduate assistant, and she credits that financial assistance with helping her and her partner move out of sub-standard housing and to pay their bills.

Even so, they had to spend money they'd socked away to a buy a house in order to stay afloat. She just received a call back for a job application, and hopes that she'll find a job before October. Mohar said, "It is so difficult every day to wake up and just not know if you are going to be able to pay your bills or what will happen."

The Associated Press contributed to this report.